Six Companies, Inc.

Hoover Dam

1931–1936

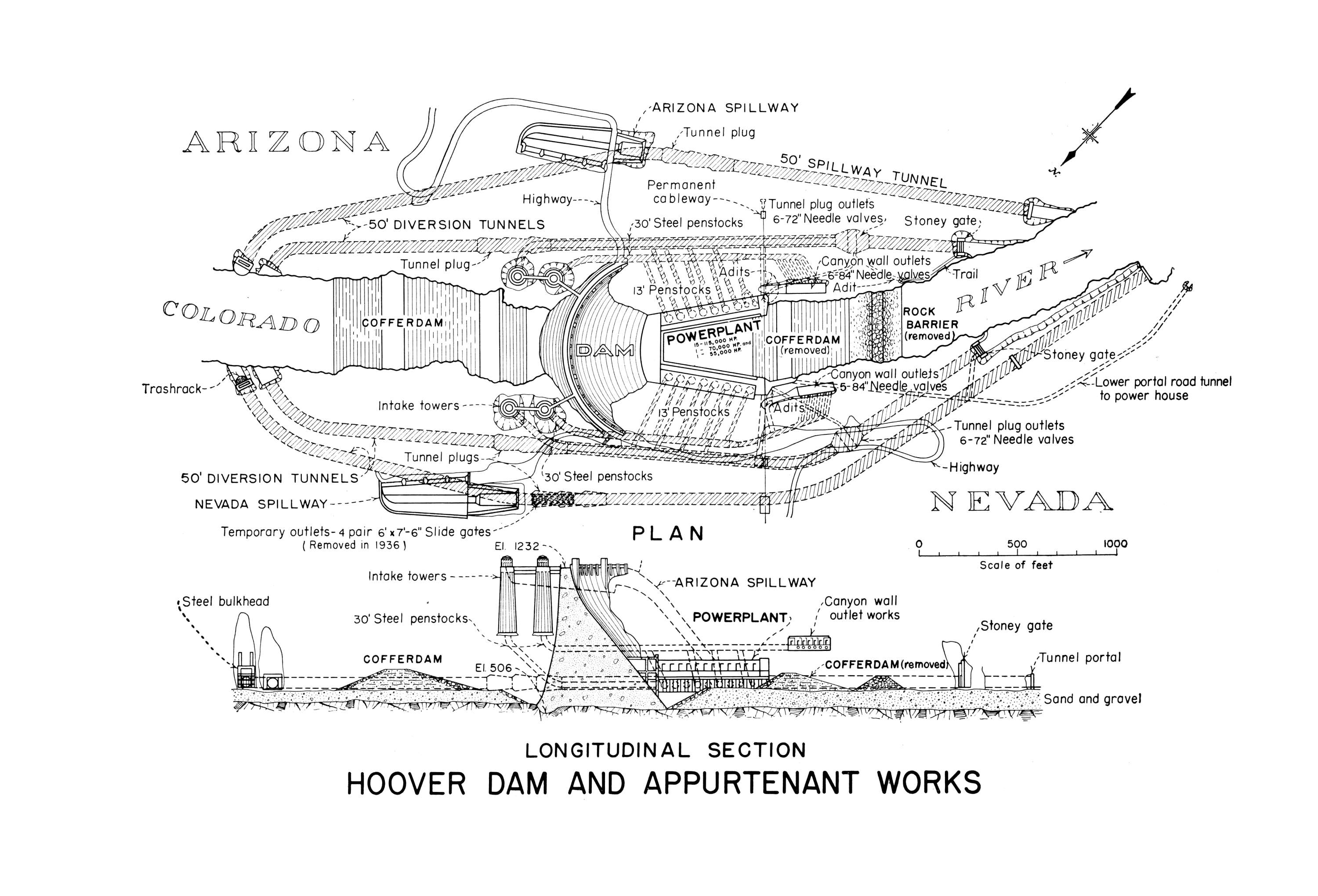

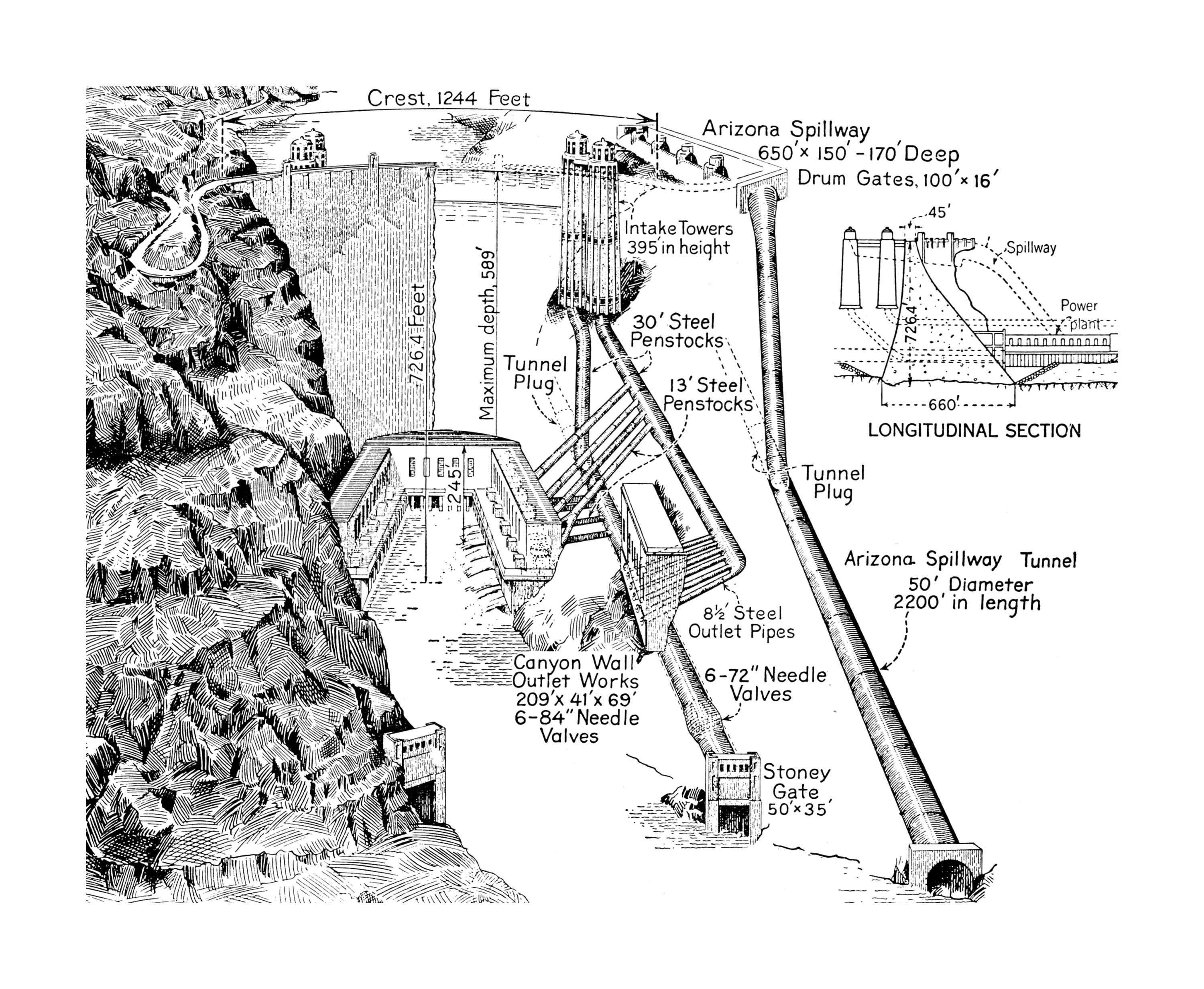

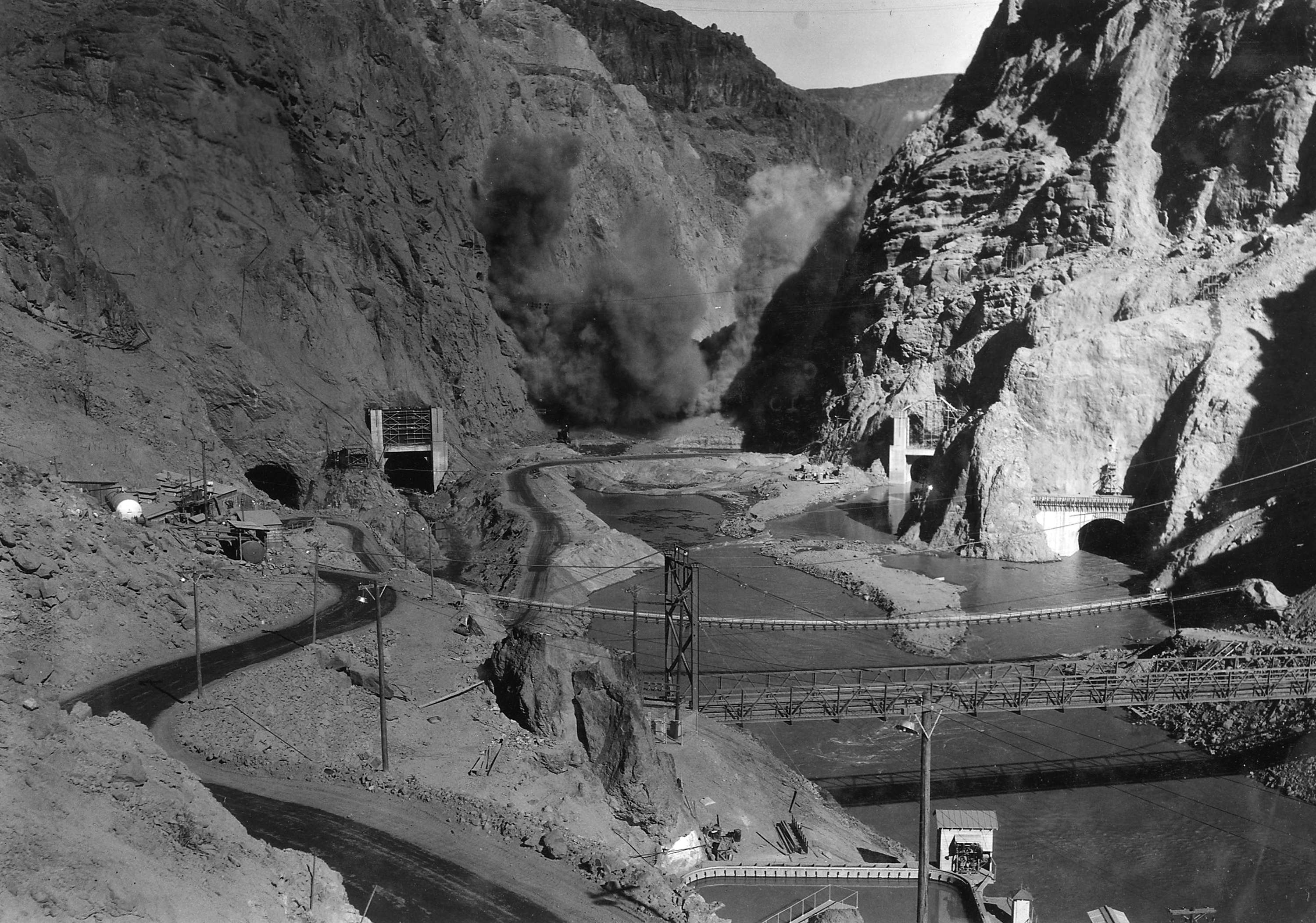

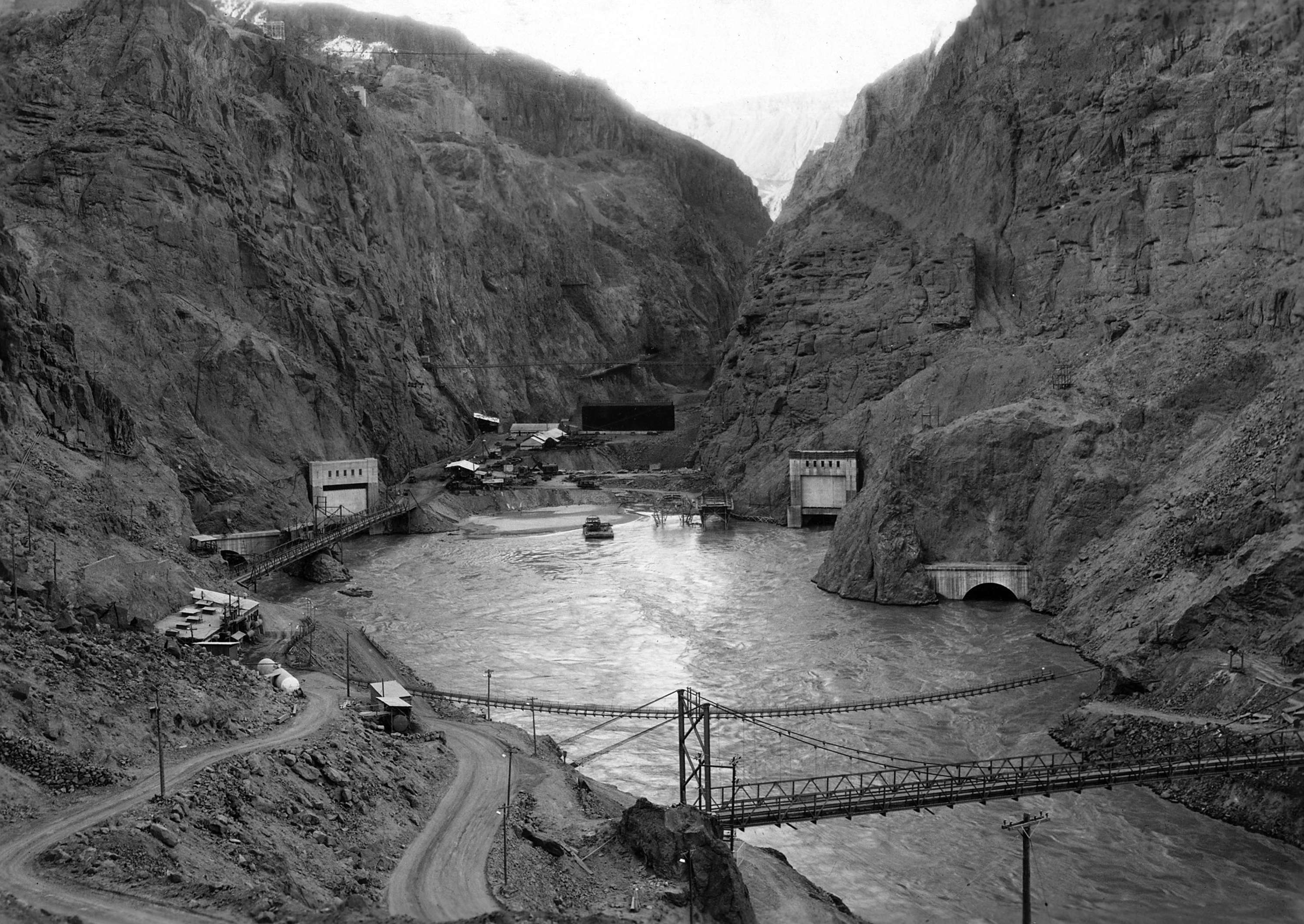

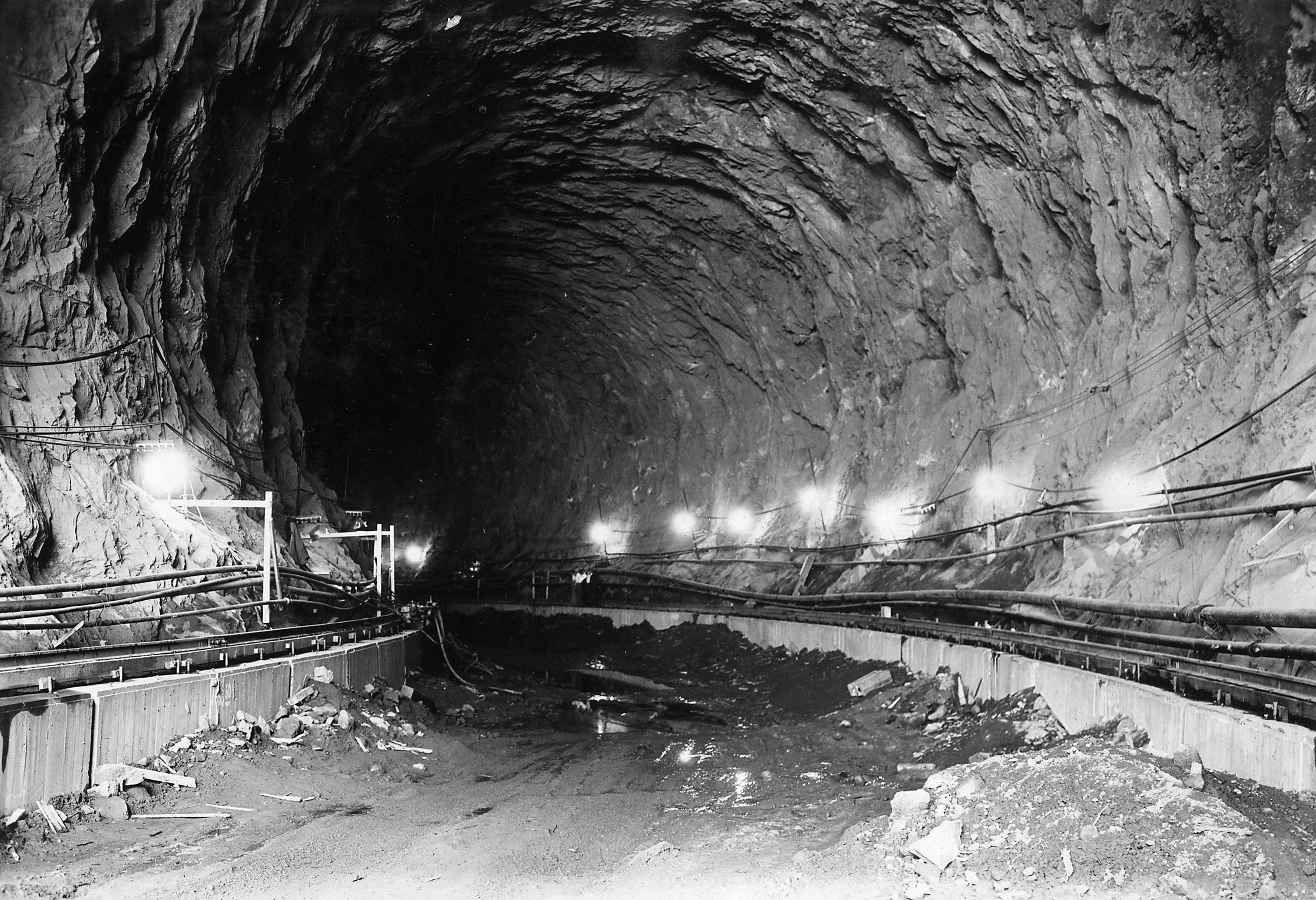

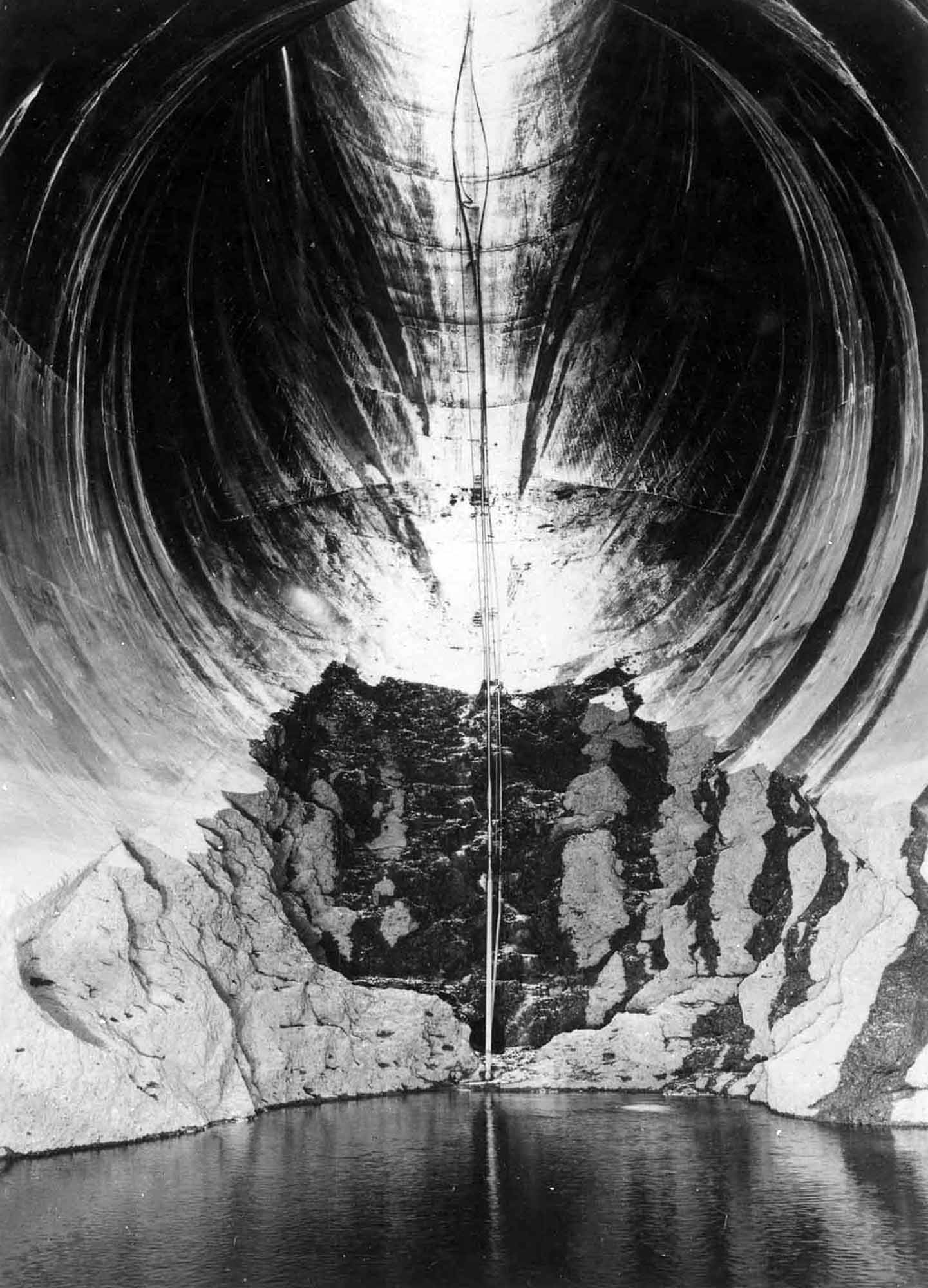

Even before Congress approved the Boulder Canyon Project, the Bureau of Reclamation was considering what kind of dam should be used. Officials eventually decided on a massive concrete arch-gravity dam, the design of which was overseen by the Bureau’s chief design engineer John L. Savage. The monolithic dam would be thick at the bottom and thin near the top, and would present a convex face towards the water above the dam. The curving arch of the dam would transmit the water’s force into the abutments, in this case the rock walls of the canyon. The wedge-shaped dam would be 660 ft (200 m) thick at the bottom, narrowing to 45 ft (14 m) at the top, leaving room for a highway connecting Nevada and Arizona.

On January 10, 1931, the Bureau made the bid documents available to interested parties, at five dollars a copy. The government was to provide the materials; but the contractor was to prepare the site and build the dam. The dam was described in minute detail, covering 100 pages of text and 76 drawings. A $2 million bid bond was to accompany each bid; the winner would have to post a $5 million performance bond. The contractor had seven years to build the dam, or penalties would ensue.

The Wattis Brothers, heads of the Utah Construction Company, were interested in bidding on the project, but lacked the money for the performance bond. They lacked sufficient resources even in combination with their longtime partners, Morrison-Knudsen, which employed the nation’s leading dam builder, Frank Crowe. They formed a joint venture to bid for the project with Pacific Bridge Company of Portland, Oregon; Henry J. Kaiser & W. A. Bechtel Company of San Francisco; MacDonald & Kahn Ltd. of Los Angeles; and the J.F. Shea Company of Portland, Oregon. The joint venture was called Six Companies, Inc. as Bechtel and Kaiser were considered one company for purposes of Six in the name. The name was descriptive and was an inside joke among the San Franciscans in the bid, where “Six Companies” was also a Chinese benevolent association in the city. There were three valid bids, and Six Companies’ bid of $48,890,955 was the lowest, within $24,000 of the confidential government estimate of what the dam would cost to build, and five million dollars less than the next-lowest bid.

The city of Las Vegas had lobbied hard to be the headquarters for the dam construction, closing its many speakeasies when the decision maker, Secretary of the Interior Ray Wilbur, came to town. Instead, Wilbur announced in early 1930 that a model city was to be built in the desert near the dam site. This town became known as Boulder City, Nevada. Construction of a rail line joining Las Vegas and the dam site began in September 1930.

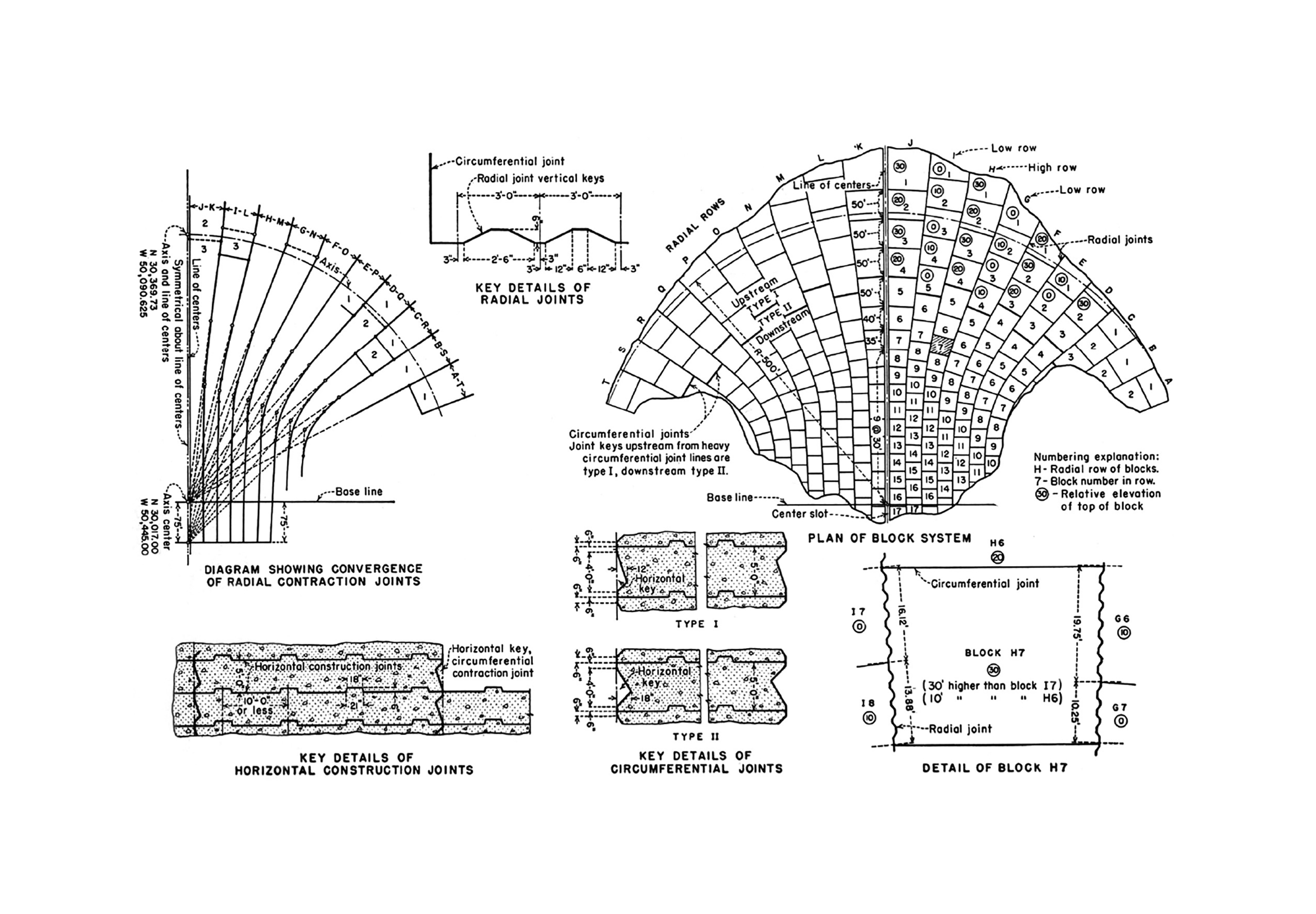

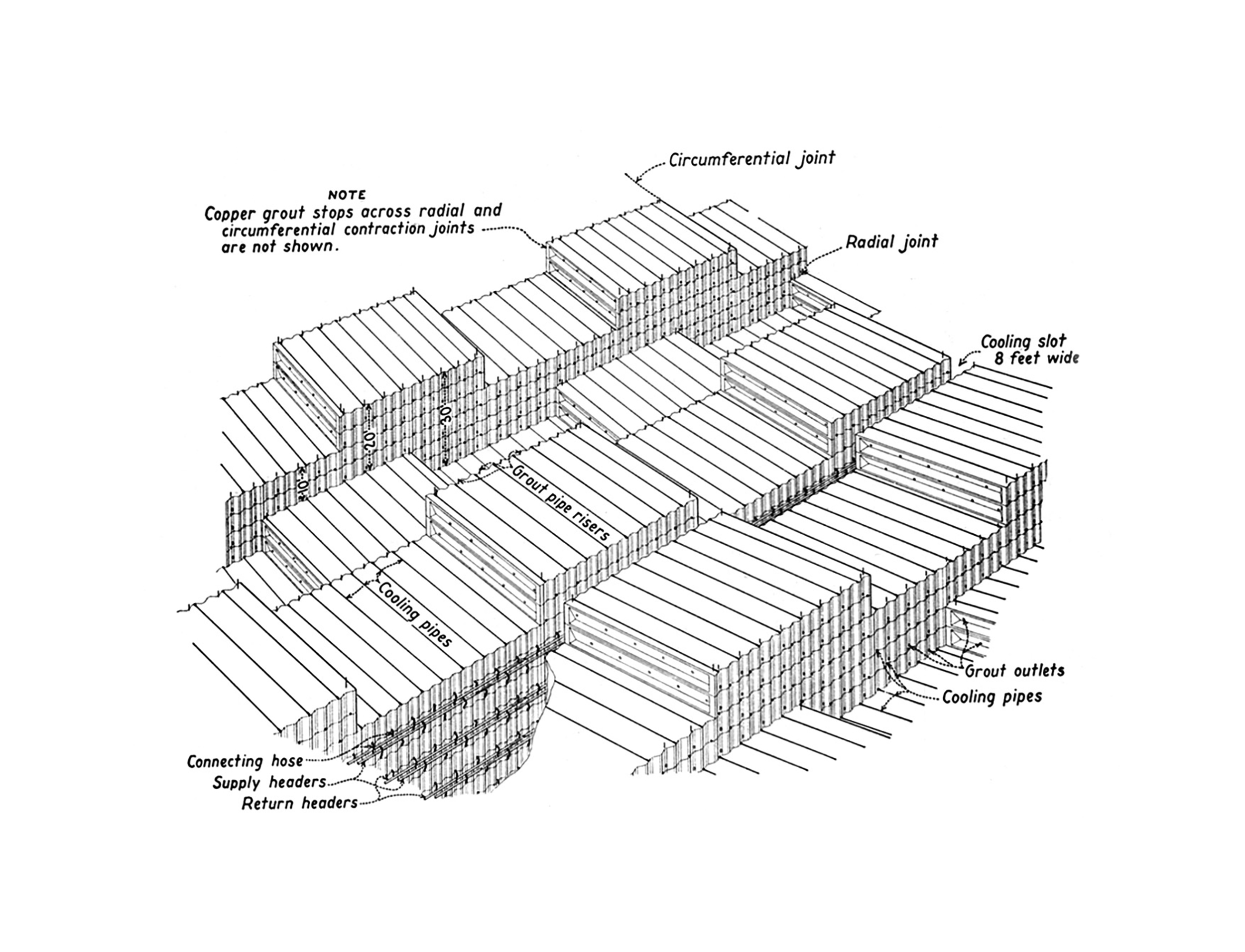

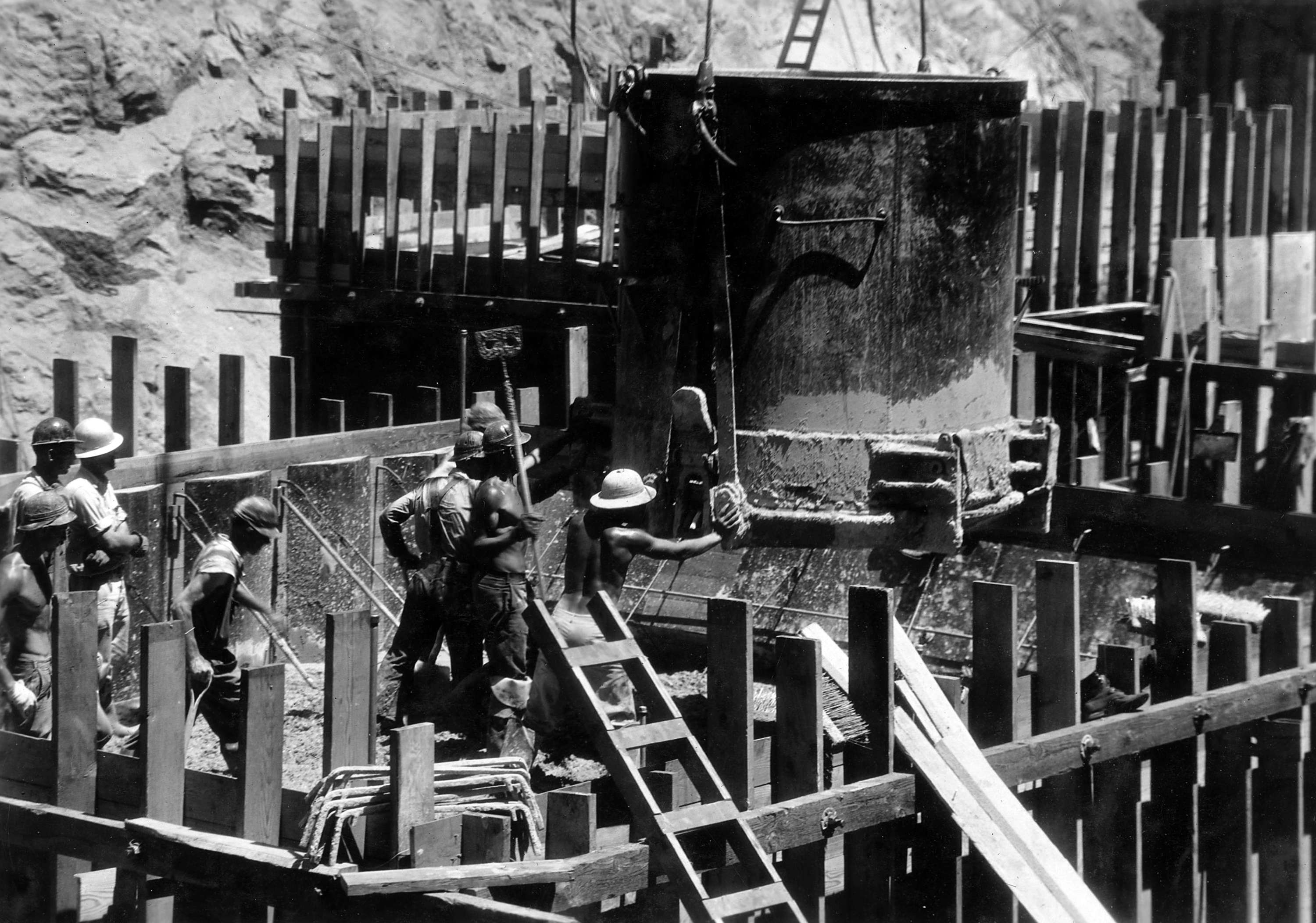

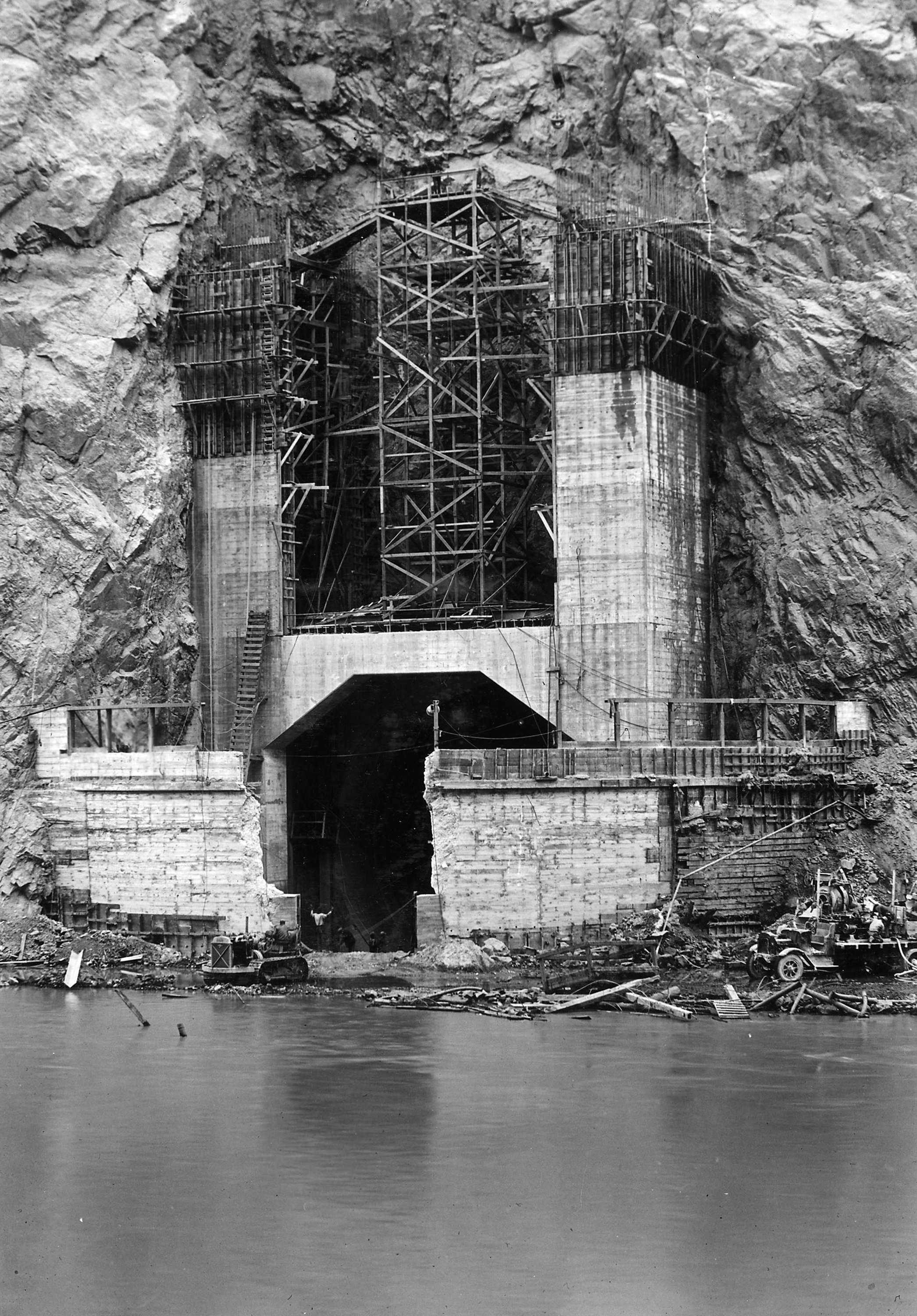

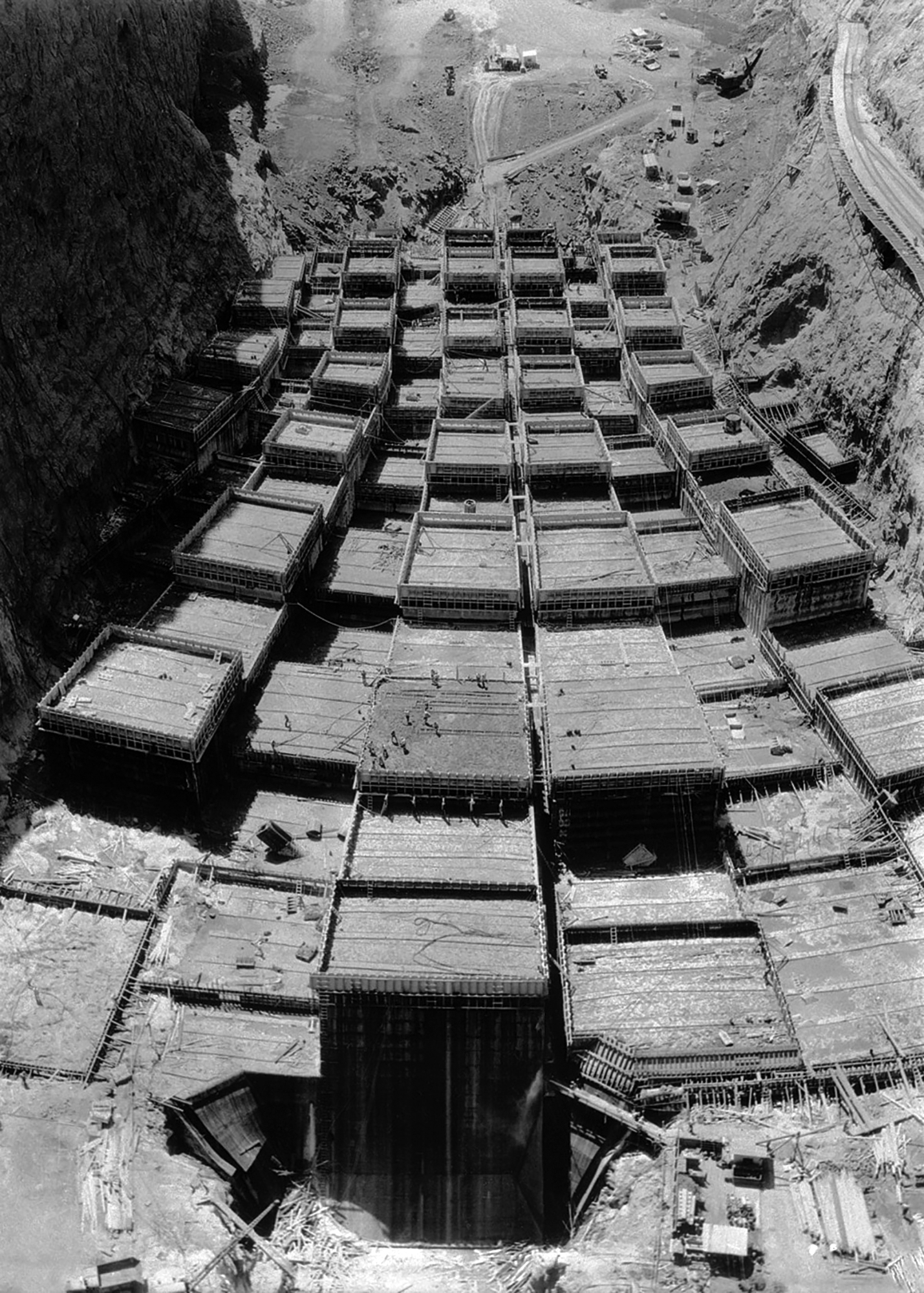

The first concrete was poured into the dam on June 6, 1933, 18 months ahead of schedule. Since concrete heats and contracts as it cures, the potential for uneven cooling and contraction of the concrete posed a serious problem. Bureau of Reclamation engineers calculated that if the dam were to be built in a single continuous pour, the concrete would take 125 years to cool, and the resulting stresses would cause the dam to crack and crumble. Instead, the ground where the dam would rise was marked with rectangles, and concrete blocks in columns were poured, some as large as 50 ft square (15 m) and 5 feet (1.5 m) high. Each five-foot form contained a series of 1-inch (25 mm) steel pipes; cool riverwater would be poured through the pipes, followed by ice-cold water from a refrigeration plant. When an individual block had cured and had stopped contracting, the pipes were filled with grout. Grout was also used to fill the hairline spaces between columns, which were grooved to increase the strength of the joins.

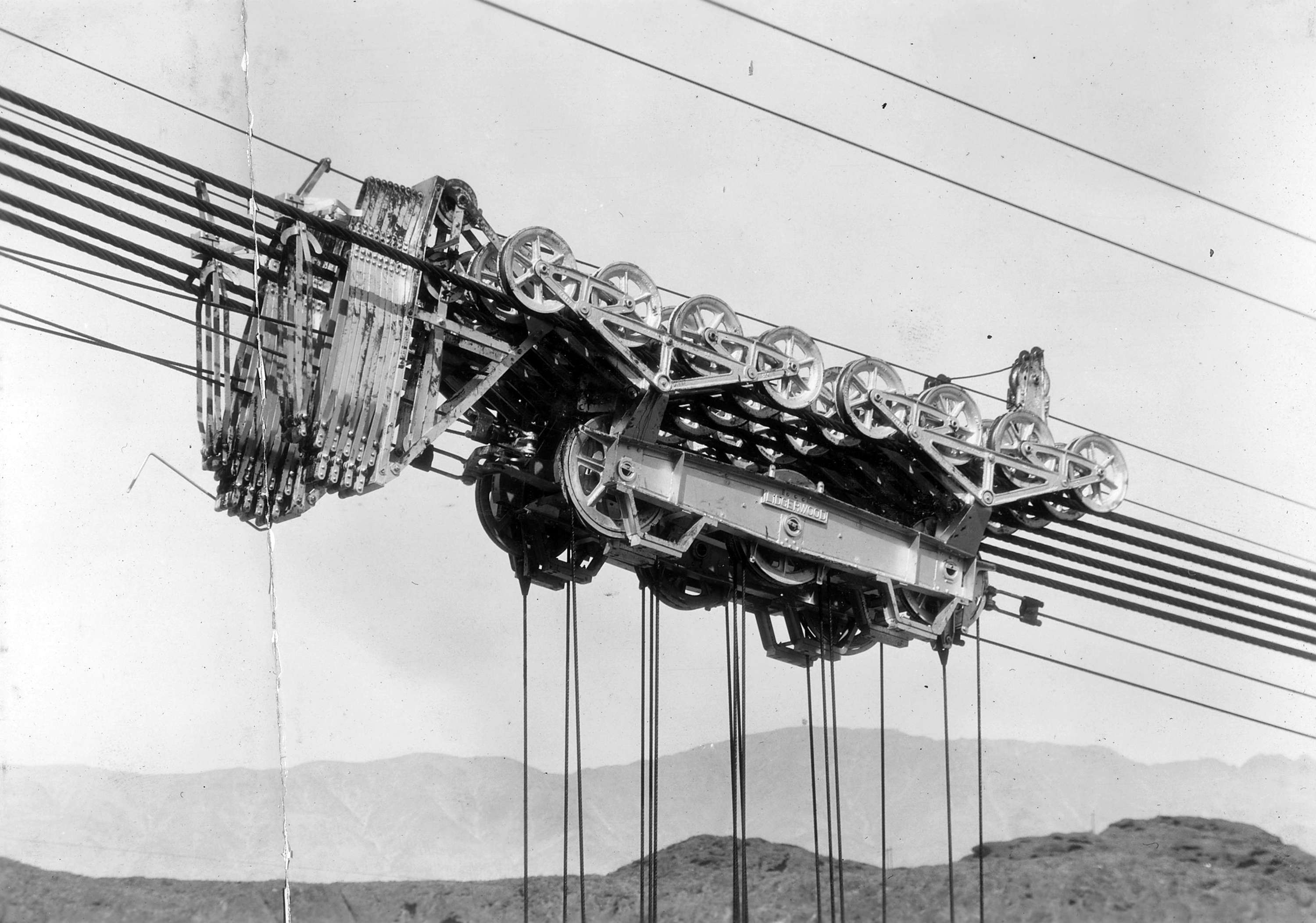

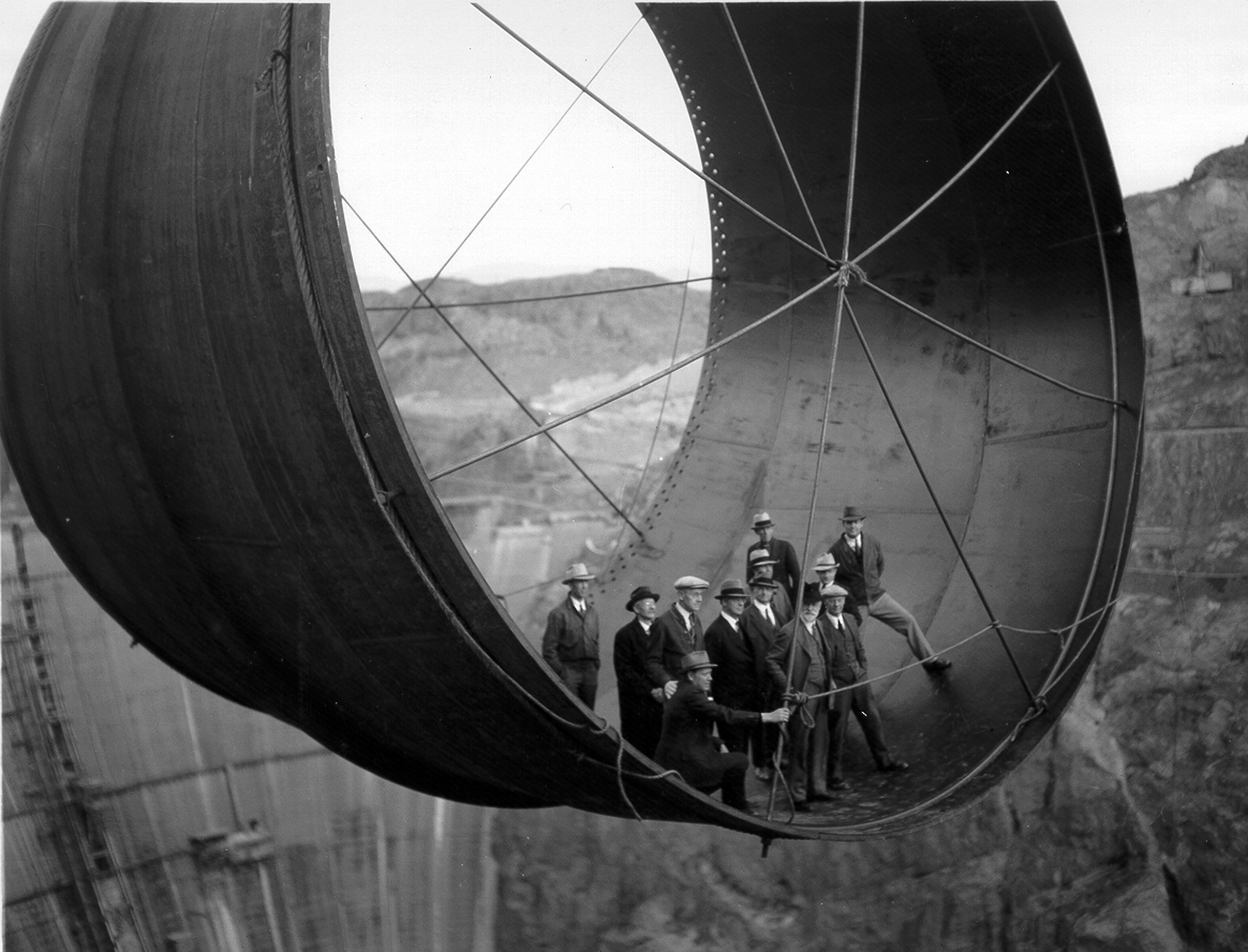

The concrete was delivered in huge steel buckets 7 feet high (2.1 m) and almost 7 feet in diameter; Crowe was awarded two patents for their design. These buckets, which weighed 20 short tons (18 t) when full, were filled at two massive concrete plants on the Nevada side, and were delivered to the site in special railcars. The buckets were then suspended from aerial cableways which were used to deliver the bucket to a specific column. As the required grade of aggregate in the concrete differed depending on placement in the dam (from pea-sized gravel to 9-inch or 23 cm stones), it was vital that the bucket be maneuvered to the proper column. When the bottom of the bucket opened up, disgorging 8 cu yd (6.1 m3) of concrete, a team of men worked it throughout the form. Although there are myths that men were caught in the pour and are entombed in the dam to this day, each bucket deepened the concrete in a form by only an inch, and Six Companies engineers would not have permitted a flaw caused by the presence of a human body.

A total of 3,250,000 cubic yards (2,480,000 cubic metres) of concrete was used in the dam before concrete pouring ceased on May 29, 1935. In addition, 1,110,000 cu yd (850,000 m3) were used in the power plant and other works. More than 582 miles (937 km) of cooling pipes were placed within the concrete. Overall, there is enough concrete in the dam to pave a two-lane highway from San Francisco to New York. Concrete cores were removed from the dam for testing in 1995; they showed that “Hoover Dam’s concrete has continued to slowly gain strength” and the dam is composed of a “durable concrete having a compressive strength exceeding the range typically found in normal mass concrete”. Hoover Dam concrete is not subject to alkali–silica reaction (ASR), as the Hoover Dam builders happened to use nonreactive aggregate, unlike that at downstream Parker Dam, where ASR has caused measurable deterioration.

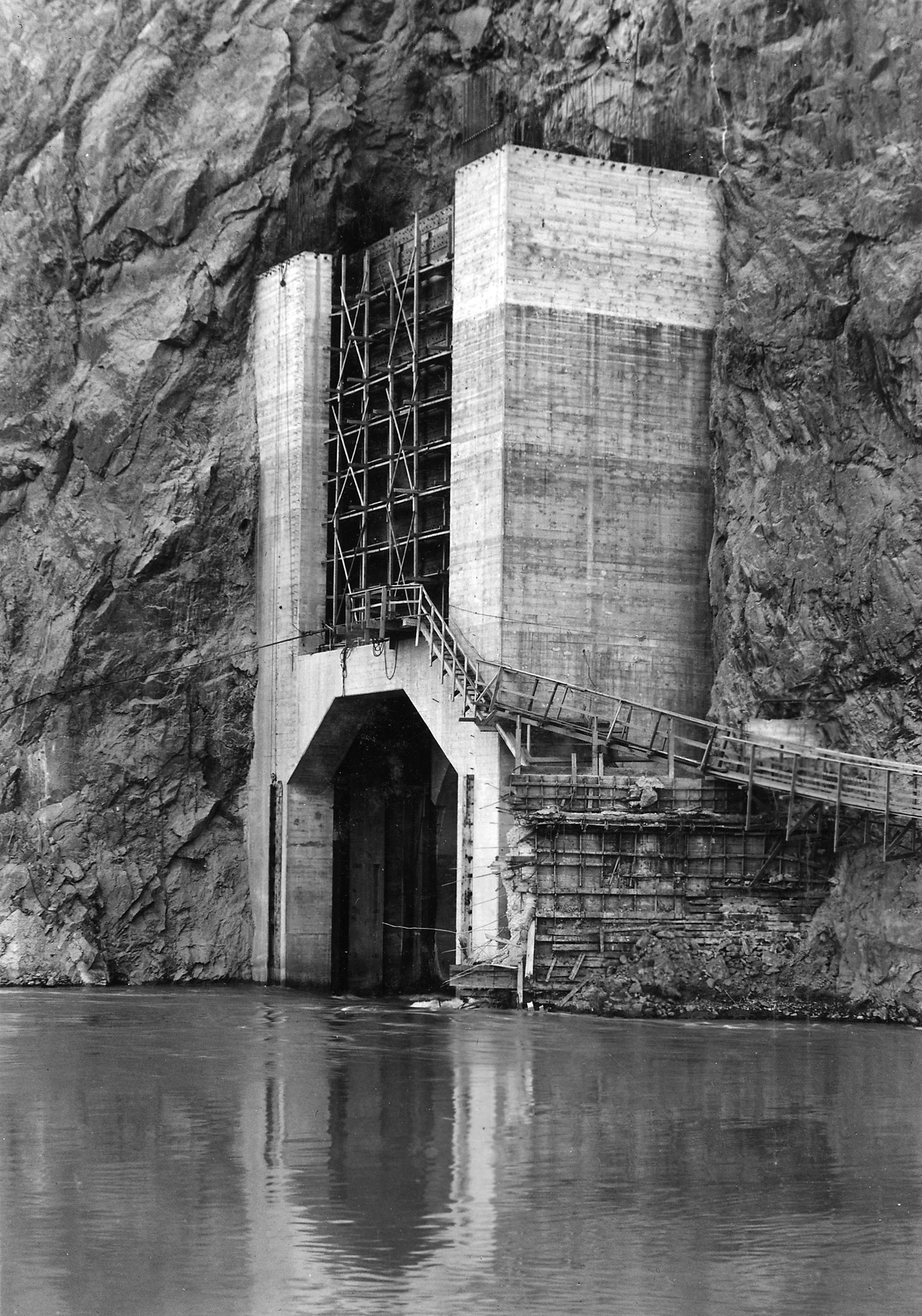

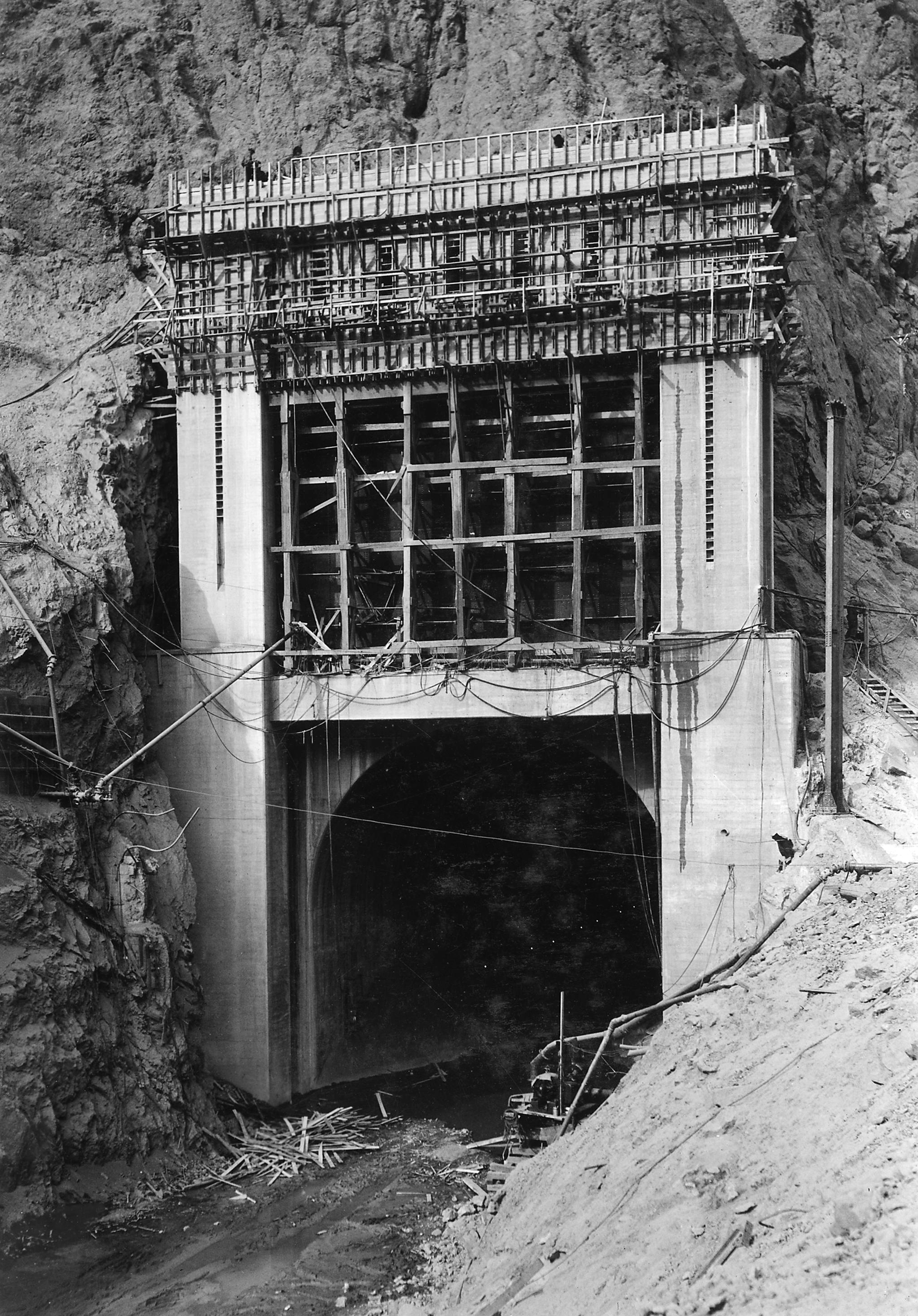

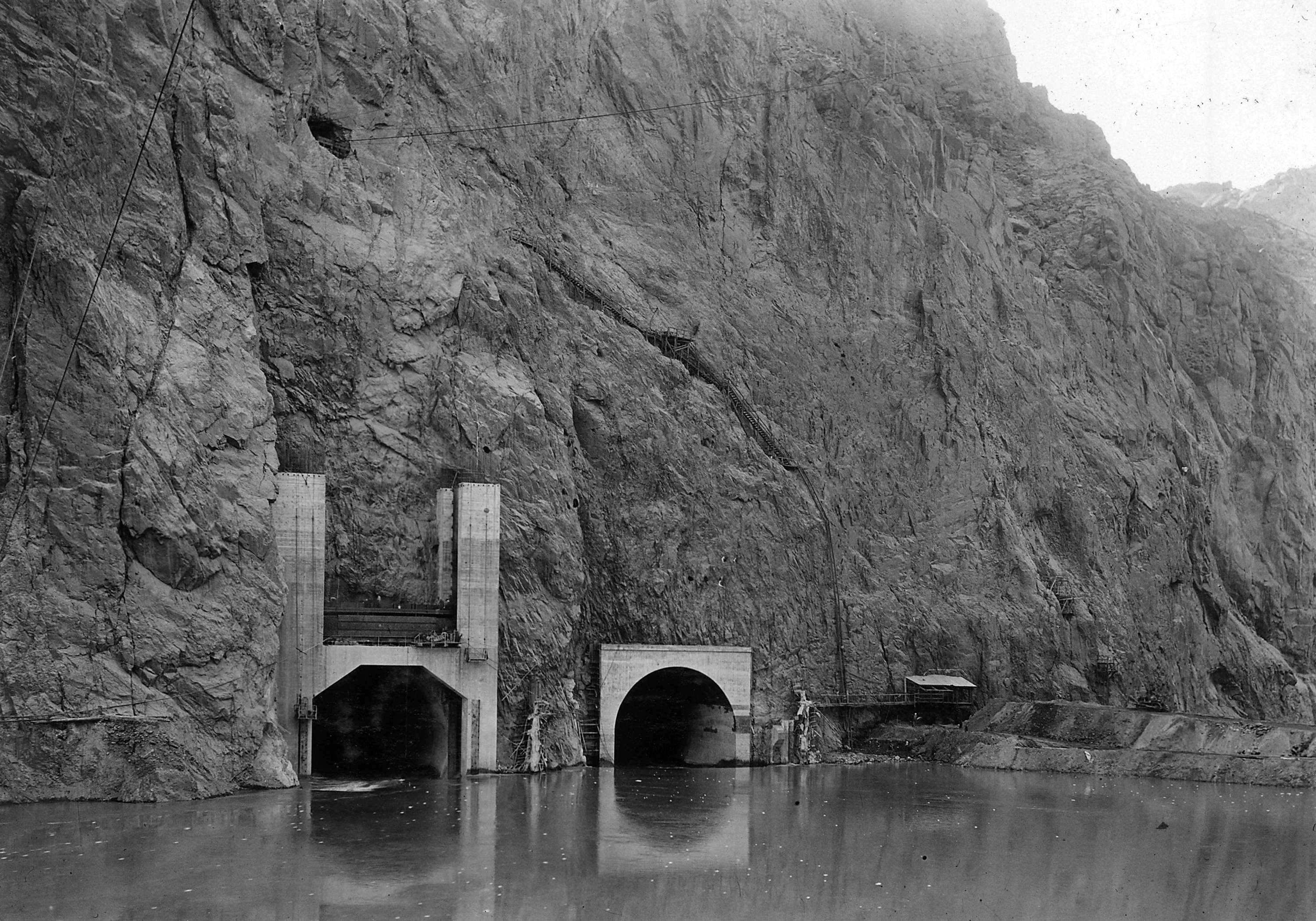

The initial plans for the facade of the dam, the power plant, the outlet tunnels and ornaments clashed with the modern look of an arch dam. The Bureau of Reclamation, more concerned with the dam’s functionality, adorned it with a Gothic-inspired balustrade and eagle statues. This initial design was criticized by many as being too plain and unremarkable for a project of such immense scale, so Los Angeles-based architect Gordon B. Kaufmann, then the supervising architect to the Bureau of Reclamation, was brought in to redesign the exteriors. Kaufmann greatly streamlined the design and applied an elegant Art Deco style to the entire project. He designed sculptured turrets rising seamlessly from the dam face and clock faces on the intake towers set for the time in Nevada and Arizona — both states are in different time zones, but since Arizona does not observe Daylight Saving Time, the clocks display the same time for more than half the year.

Lieu: Clark County NV, USA

Type: Barrage, Infrastructure

Cost: $49 million (1931 budget) - $639 million (2016 dollars)

Owner: United States Government

Operator: U.S. Bureau of Reclamation

Type: Concrete Gravity-Arch

Impounds: Colorado River

Height: 726.4 ft (221.4 m)

Length: 1’244 ft (379 m)

Width (Crest): 45 ft (14 m)

Width (Base): 660 ft (200 m)

Volume: 3’250’000 cu yd (2’480’000 m3)

Photography: Ansel Adams - Julius Shulman - Mitch Epstein

Text: Wikipedia

Publié: Mars 2018

Catégorie: Architecture